The Case for High Speed Rail: Chicago to the Twin Cities

Revolutionizing Midwest Travel: Connecting the Twin Cities and Chicago in Just 3 Hours

It’s May of 2024, and the much-studied Borealis rail service launches its lone daily trip between Chicago and St. Paul. With five cars pulled by a single diesel engine, it covers the 411-mile journey in a sluggish 7 hours and 20 minutes—an average of just 56 miles per hour.

Yet, despite its slow speed and limited service, the Borealis defies expectations. Projected to carry 124,000 riders annually, it attracts 100,000 riders in its first 22 weeks—beating projections by nearly 90%.1

This isn’t a new phenomenon in U.S. transit history. Even as one of the world’s greatest passenger rail systems crumbled mid-century, the demand for rail service never disappeared. Yet, while the USA pours $200 billion annually into highways2, high-speed rail projects are dismissed by governors as “boondoggles,” leaving regions like Chicago and Minneapolis with embarrassingly inadequate rail options.

If we had invested in high-speed rail as recommended by the 1991 Tri Rail Study study, Chicago and Minneapolis could now be connected in just three hours, serving 11 million passengers annually. Instead, the region remains mired in slow trains and missed opportunities.

The Profile of the Corridor:

While Amtrak’s current service circumvents Madison, nearly all high-speed rail studies and proposals have included Wisconsin’s capital. Excluding Madison from a direct high-speed rail route—one that could connect the state’s two largest cities in just 25 minutes—is a significant oversight, in my opinion. Madison’s inclusion is critical, not just for its political and economic importance as the state capital, but for its potential to boost ridership and connectivity across the region.

To understand the full potential of the Chicago-to-Minneapolis corridor (which differs slightly from Amtrak’s existing routes), let’s take an inventory of the key cities/metros high speed rail would serve.

How does existing rail compare?

The lack of high-speed rail in the United States is not a new revelation, but the inefficiency of current services is staggering. Take the Borealis route: a 440-minute train journey to connect three metropolitan areas with a combined GDP nearly three times that of Sweden is a stark reminder of America’s lagging infrastructure. Even the Milwaukee-to-Chicago segment takes 15 minutes longer today than the Milwaukee Road’s service did 80 years ago.

By comparison, a high-speed rail service between Chicago and Minneapolis could transform travel in the region. With Italy’s high-speed rail speeds, the trip would take just 3.5 hours, while Germany’s speeds could cut the time to 2 hours and 19 minutes—a reduction of 53% or more. As shown in the chart, this would bring the U.S. in line with world-class rail systems like those in France, Japan, or Spain.

Why Should This Corridor Get High-Speed Rail?

The Fundamentals are Great: In 2011, the America 2050 project evaluated 7,870 rail corridors under 600 miles, scoring them on 12 criteria like population, employment, transit connectivity, air travel demand, tourism, and congestion. Out of all the corridors longer than 300 miles, only three achieved the highest score of 16.66: Los Angeles to Las Vegas, Los Angeles to San Francisco, and Chicago to Minneapolis. Unlike the other two, Chicago to Minneapolis remains neglected, with no high-speed rail in development and only painfully slow Amtrak service. It’s a glaring missed opportunity.

A High-Demand Air Corridor: The Chicago-to-Minneapolis corridor is one of the busiest domestic air routes in the Midwest, with 1.65 million passengers flying annually (2009).3 There are 22 daily flights between Minneapolis and Chicago alone, highlighting significant demand for fast, efficient travel. High-speed rail could replace much of this short-haul air traffic, reducing congestion and freeing airport capacity for longer flights. Additionally, direct connections to O’Hare could open new markets and reduce inefficiencies, such as the seven daily round-trip flights between Milwaukee and Chicago.

The Region is an Economic Powerhouse: This corridor connects four major cities—Chicago, Milwaukee, Madison, and the Twin Cities—with a combined GDP of $1.45 trillion. To put that in perspective, this region’s economy is nearly twice as large as Switzerland’s, a country with 10,000 daily train trips4. Investing in high-speed rail here would enhance regional productivity, reduce travel times, and link economic hubs in a way that unlocks even greater growth.

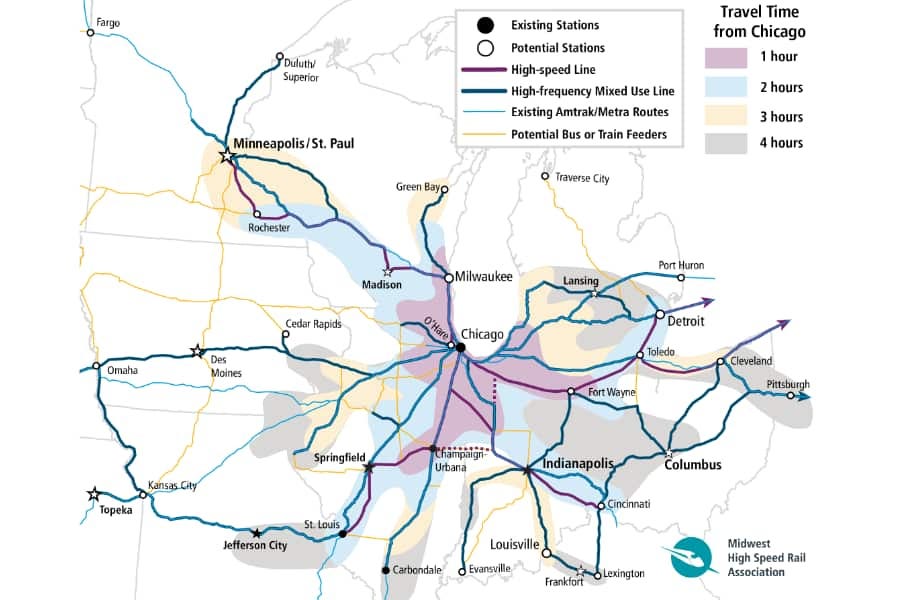

The Chicago Hub Vision - The long-studied Chicago Hub Plan envisions a 220 mph high-speed rail backbone originating in Chicago, supported by regional train services and feeder bus networks to extend connectivity across the Midwest. This integrated system would transform Chicago into the Midwest’s central rail hub, allowing seamless travel to major cities in the region. Chicago and Minneapolis airports together serve 7.9 million passengers annually traveling within this region—many of whom could switch to rail for faster, more efficient journeys.5 While there may be little direct demand for high-speed rail between smaller city pairs like Rochester, MN, and Springfield, IL, the hub-and-spoke model means passengers could make such connections easily with one transfer in Chicago. Estimates show that the Minneapolis-to-Chicago corridor alone would account for more than a third of the projected 44 million annual passengers on this system. Launching this route first would not only address one of the most in-demand corridors but also jumpstart the broader Chicago Hub network, accelerating its construction and delivery. (220 mph backbone shown in hot pink)

It Would Make Scott Walker Mad: Former Governor Scott Walker, who denied high-speed rail funding under the Obama Administration, has long been an opponent of rail and rapid transit. While the success of the Borealis can be attributed to the Evers administration, it would be encouraging to see high-speed rail succeed despite opposition from elected officials who prioritize highways. Demonstrating the effectiveness of this technology in the U.S. is essential to building the political capital needed to expand it nationwide.

What Would High-Speed Rail Look Like?

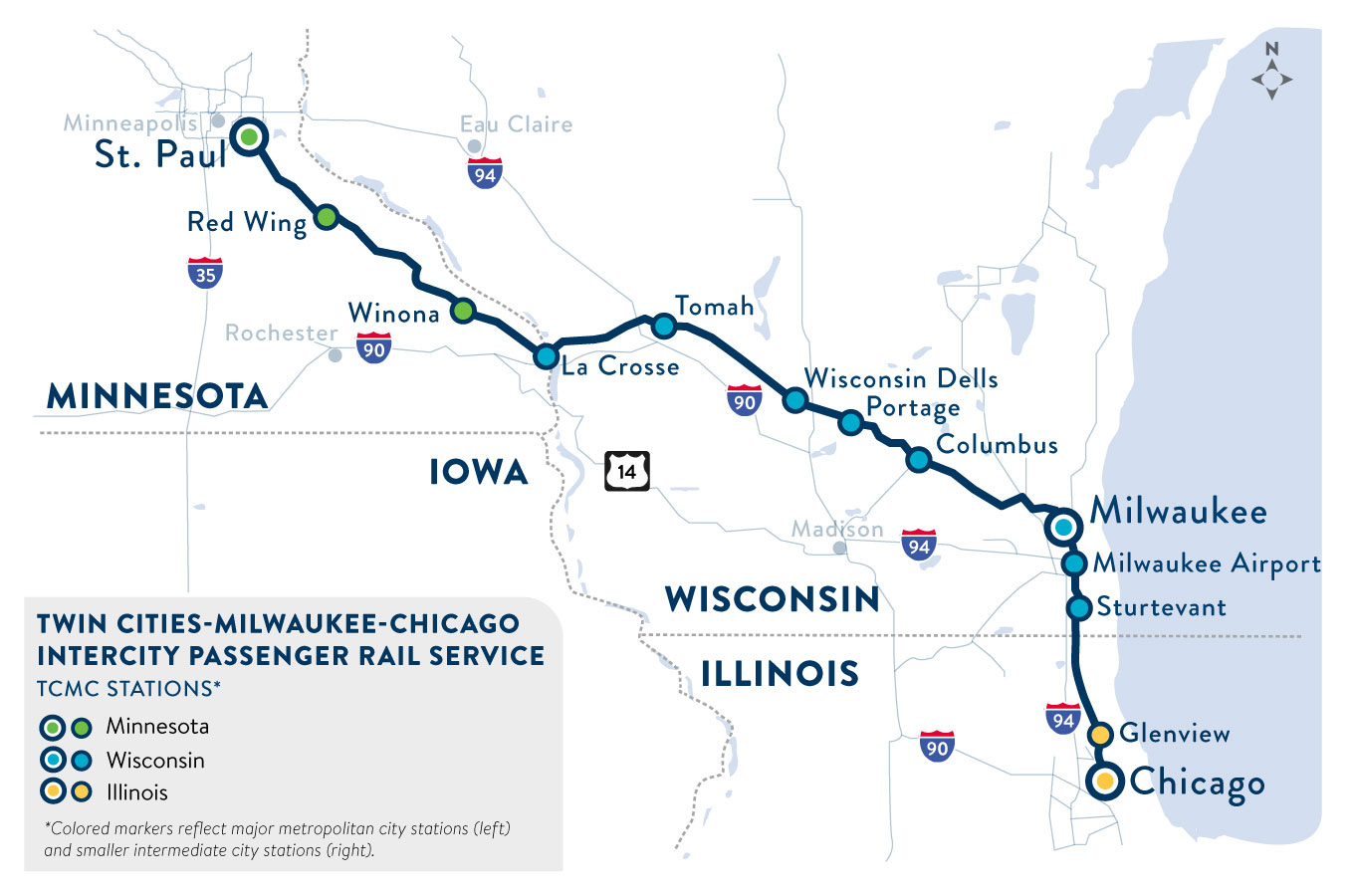

Based on the analysis of the SNCF proposal for Midwest high-speed rail (HSR) in 2009 and subsequent studies by the Midwest High Speed Rail Association in 2011, the optimal routing for a Chicago-to-Minneapolis HSR corridor should include stops in Milwaukee, Madison, La Crosse, and Rochester. Secondary stops at Milwaukee Airport (MKE) and O’Hare International Airport have also been studied, though the latter is beyond the scope of this piece.

While routing through Eau Claire would provide a more direct path, the challenges of building a new bridge over the St. Croix River make this option less feasible.

Informed by these studies and my own analysis, the proposed route aims to minimize its footprint, enable maximum speeds of 150–220 mph where possible, and provide the best passenger experience. This rail line must be electrified, and any segment exceeding 125 mph must be fully grade-separated with a dedicated right-of-way (ROW) to meet safety and operational standards.

The estimated average travel speed between Chicago and Minneapolis: 133 mph.

(Go to the Alignment Section at the bottom if you’re interested on the technical routing that’s based off both studies and my own opinion.)

Frequency

Trains would operate on a clockface schedule, with departures every half hour or hour depending on the time of day. According to the latest AECOM study, the system could support 25 trains in each direction daily—matching the frequency of direct high-speed services between Paris and Marseille.

Speeds

According to FRA and international standards, building dedicated trackway and grade-separated infrastructure for train speeds over 125 mph results in only minimal differences in cost between systems designed for maximum speeds of 150 mph and 220 mph. The primary distinction lies in curve radii—5 miles for 220 mph versus 2 miles for 150 mph—and the additional traction power required for higher speeds.

AECOM’s 2010 study found that the capital outlay for a 150 mph system was only about 10% lower than that for a 220 mph system. Considering this marginal difference, reducing travel time between Minneapolis and Chicago by an additional hour for a modest cost increase makes a 220 mph system the clear choice.

It’s important to note that this does not assume the train will cruise at maximum speed for the entire route. Rather, the system would be designed to enable such speeds on segments where it is feasible, ensuring maximum efficiency and time savings.

Instead of the current Borealis taking 7 hours and 24 minutes, travel times could be reduced by 50% or 63% with 150 mph and 220 mph service, respectively.

Given that a 10% increase in costs would shave an additional hour off the trip, it makes sense to prioritize the 220 mph option for this project.

Cost

Building high-speed rail is a significant investment. For this 455-mile corridor, adjusted 2024 estimates place the total cost at $39.787 billion, or $87.6 million per mile, including a 35% contingency. However, much of this contingency accounts for inefficiencies and uncertainties in U.S. infrastructure projects. By adopting international best practices, the final cost could likely be reduced—an approach the U.S. must consider to build efficiently. (More on effective HSR construction practices in a future piece.)

The 220 mph service is projected to add $7.8 billion annually to the region’s GDP, alongside an economic boost of $13.8 billion in additional activity.

To put the costs into perspective, the Chicago-Minneapolis high-speed rail line, as proposed by SNCF, would take 12 years to build, with annual construction costs of $3.315 billion if the total project cost were evenly distributed. This represents just 4.8% of the annual federal aid highway budget (based on 2023 figures)—a negligible amount within the country’s discretionary budget.

Ridership

Modeling for the corridor projects that within 5 to 10 years of operation, the Chicago-to-Minneapolis high-speed rail route would attract 15.844 million annual passengers. To put that into perspective, the Los Angeles to Las Vegas high-speed rail project is to move 11 million passengers.6

In total, if built, the full 220 mph Midwest HSR network is expected to serve 43.664 million passengers annually, with the Chicago-to-Minneapolis route accounting for 36% of this ridership. This makes it one of the most critical corridors for the success and political sustainability of the broader system.

Conclusion

The Chicago-Minneapolis corridor is more than a rail project—it’s a symbol of what the U.S. could achieve if it embraced world-class infrastructure. The benefits are clear: faster travel, economic growth, reduced car dependency, and revitalized regional connections. The success of services like Brightline and even the modest Borealis prove that Americans are ready for better rail options.

Standing in the historic beauty of Chicago’s Union Station or St. Paul Union Depot, we’re reminded of a time when trains were the backbone of the nation’s economy. Investing in high-speed rail isn’t just about catching up with the rest of the world—it’s about reclaiming that legacy and building a future where rail travel drives prosperity once again.

(Author’s Note: I’d like to create a replicable template for conducting these HSR corridor case studies. If you have any comments or suggestions for refinement, I’d greatly appreciate your feedback.)

Appendix: The Proposed Alignment

(You can ignore this section if you’re not interested in the technical alignment)

The proposed alignment follows analysis from the SNCF proposal for Midwest high-speed rail (HSR) in 2009 and subsequent studies by the Midwest High Speed Rail Association in 2011, as well as my own opinion.

Chicago - Milwaukee: The route would begin at a significantly expanded and reconfigured Chicago Union Station, requiring new aerial electrified tracks adjacent to METRA’s MD-N line. Grade separations and flyovers would be needed to ensure uninterrupted service. At Wadsworth, the dedicated right-of-way (ROW) would either follow the existing Amtrak alignment or on the I-94 corridor, depending on which option offers greater speed and feasibility. From there, the train would continue, stopping at Milwaukee Mitchell Airport (MKE), before following the route to the Milwaukee Intermodal Station, where additional track upgrades and modifications to the station are likely necessary.

Milwaukee - Madison: West of Milwaukee Intermodal Station, existing tracks would be used up to the Menomonee River near Waukesha. From there, a new two-track dedicated ROW would follow the I-94 corridor, either in the median or alongside it, similar to the Brightline alignment between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. The largely rural nature of this stretch allows for track design supporting speeds of up to 220 mph.

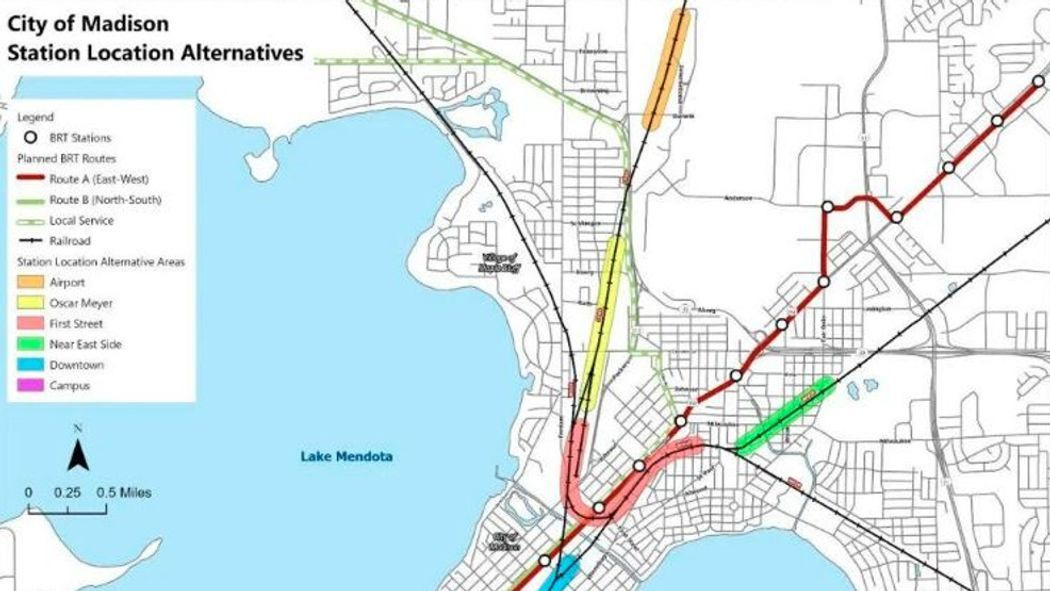

Closer to Madison, trains would use the Wisconsin & Southern ROW to approach a new East Washington Street Station in downtown Madison. While this slower approach isn’t ideal, it provides essential connectivity. The station’s location would align with the red-shaded area identified in the Madison Station Location Study. This is where my proposed alignment differs from previous studies which want to stop more north of Downtown Madison.

Madison - Rochester: Leaving Madison, new tracks adjacent to the M&P Subdivision would continue north, transitioning to a new dedicated ROW parallel to I-90 or the existing Amtrak route, depending on ROW acquisition feasibility and curve constraints. The route would stop at La Crosse’s Amtrak station, north of downtown, which would require upgrades and new tracks to connect with local Amtrak services like the Borealis and Empire Builder.

The most challenging segment follows, where the ROW must navigate the hilly terrain of Great River Bluffs State Park. This will likely require a combination of tunnels, retained cuts, and embankments until rejoining I-90. From there, the route would continue along I-90 and I-14, utilizing the Waseca Subdivision ROW where possible. In downtown Rochester, an aerial station with grade separation would be needed.

Rochester - Minneapolis: The alignment would reactivate the abandoned ROW now known as the Douglas State Trail, extending it to I-52 with new tracks. From there, a southern approach would lead to St. Paul Union Depot, following Union Pacific tracks with a new aerial alignment. After reaching St. Paul, the route would extend to Minneapolis’s Target Field Station, the final terminus. This station would integrate with existing light rail, NorthStar Commuter Rail, and future connections to Duluth and other parts of Minnesota.

https://media.amtrak.com/2024/10/borealis-ridership-reaches-100000-passengers-in-22-weeks/

https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/state-and-local-backgrounders/highway-and-road-expenditures

https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/rpa-org/pdfs/2050-High-Speed-Rail-in-America.pdf

https://www.s-ge.com/en/article/news/20182-ranking-trains?ct#:~:text=With%20a%20total%20rating%20of,the%20trains%20are%20very%20punctual.&text=The%20ratings%20of%20the%202017,ratings%20in%20the%20safety%20category.

https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/rpa-org/pdfs/2050-High-Speed-Rail-in-America.pdf

https://nypost.com/2024/04/22/business/work-starts-on-first-high-speed-train-in-us-between-la-and-vegas/

Where are you getting the average speed for Beijing Guangzhou? It does 2230 km in 7:17 (G79, G80) for an average of 306 kmh. So it would do a 441 mile route in 139 min, not 159.

100% agree with the argument (as a regular rider of the Borealis to Madison by getting a ride from Columbus, it's still far better than driving or taking the bus despite the time difference). I will be very curious on the political viability of this though - it seems like it would require so more coordination to actually achieve given the states involved (plus having to solve the Madison problem).

I hope to see it though! Feels like a perfect example of a high speed opportunity.