Why Building Transit Costs So Much (Part 1): We Overbuild

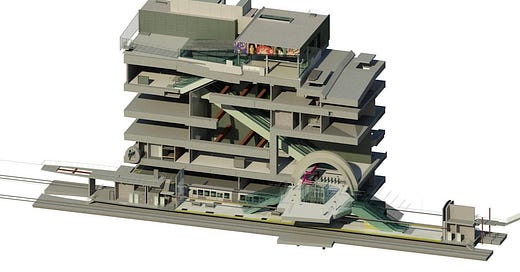

Bigger isn't better when it means building less

(A must-read and source material: Transit Costs and Understanding the Costs of Transit Construction)

No single issue threatens the proliferation of public transit in the U.S. and Canada more than the time and cost it takes to build it.

Projects like California High-Speed Rail or New York’s Congestion Pricing face fierce backlash not just because of what t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Transit Guy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.