The Least-Ridden Train in America—and Why That’s No Surprise

What Nashville’s WeGo Star Tells Us About Building Better Regional Rail

You're standing in the lobby of Lyon-Part-Dieu station, looking up at a departure board displaying 23 domestic and international train lines—routes that can take you to Paris, London, Frankfurt, Turin, and Barcelona without a transfer. If you're not looking for an intercity or high-speed train, you can still choose from 12 tram lines, four metro lines, and a network of local and regional buses.

Now, compare that to Nashville, a city and metro area of similar size. Here, you’ll find just 27 bus routes serving a city nearly 40% larger than Lyon, and only eight of those routes run more frequently than every 15 minutes. As for rail? The metro’s only rail service, the WeGo Star, is the least-ridden commuter rail line in the country, averaging just 482 weekday riders.

With little political will at the state or regional level to restore rail service since the 1979 cancellation of Amtrak’s Floridian, Nashville’s Chamber of Commerce and Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) took matters into their own hands. They attempted to implement a commuter rail pilot "on a budget." One government official even quipped, "If it happens, it happens, but we aren’t going to push for it."

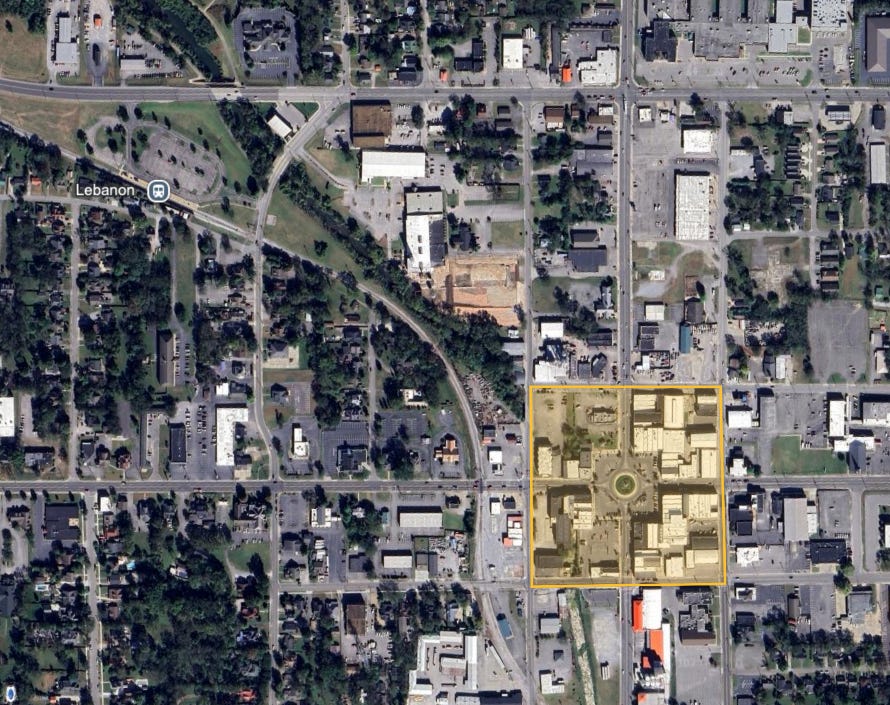

Armed with a $40 million budget ($63 million adjusted for inflation), they launched the Music City Star (now WeGo Star)—a 32-mile rail service between Nashville and Lebanon with six stations on tracks owned by the Nashville and Eastern Railroad. The hope? That this pilot would garner support for five additional routes, eventually forming a rail system shaped like a star.

The project was so constrained by budget that the agency modified old parking ticket machines—at $17,000 apiece—to serve as ticket vending machines, rather than spending $500,000 per machine for full-service ticketing.

Since its inception, the WeGo Star has never met its ridership targets, and the much-anticipated regional rail system never materialized—even though voters approved a $3 billion BRT and infrastructure expansion bill in 2024.

Why it Obviously Performs Badly

The formula for making transit productive is straightforward and universal. If the WeGo Star were successful in its current form, it would defy the principles that the entire industry knows to be true, and transit planning would be haphazard.

Riders respond to convenience, and this service is anything but.

1. It Serves Nothing

Given that all rail lines in and out of Nashville with meaningful population density are owned by CSX—a notorious opponent of transit and passenger rail—the WeGo Star followed the path of least resistance. Instead of choosing a route that would serve the most people, they chose one that was simply the easiest to implement. The result? A rail line that avoids nearly all population centers.

The corridor's population density is just 867 people per square mile, far lower than the 4,900 in Nassau County, NY, or the 2,800 in DuPage County, IL, both of which support strong regional rail networks.

Take Martha Station, for example—it serves just 11 homes within a half-mile walk of the station.

Station placement matters just as much as corridor selection. Take Lebanon, the train’s terminus. The station is 0.6 miles from the town center, the only walkable area along the entire 32-mile corridor outside of Nashville.

If a rider wants to take the train to Lebanon, parking at a station and then walking nearly 20 minutes to their final destination makes little sense. At that point, it’s simply more convenient to drive.

What Good Regional Rail Needs:

Density along the corridor, or a clear plan to build it in concert with the capital investment.

Minimizing reliance on freight ROW whenever possible. Freight railroads were built to avoid population centers and serve industry, which is the opposite of what good passenger transit needs.

Strategic station placement. Christof Spieler makes a great point: “If people aren’t outraged about your transit project, it’s probably not serving population centers.” Stations should be located in the most walkable, dense areas to maximize ridership potential.

2. It Is Not Well Connected

Of the six stations outside of Nashville, only two have bus connections, and both are served by the same bus route—which just happens to run parallel to the train. This presents two major flaws:

If Bus Route 6 runs more frequently than the train and serves three of the same stations, why would anyone take the train instead?

If the only way to access these stations is by car, why not just drive to the final destination instead of adding an unnecessary transfer?

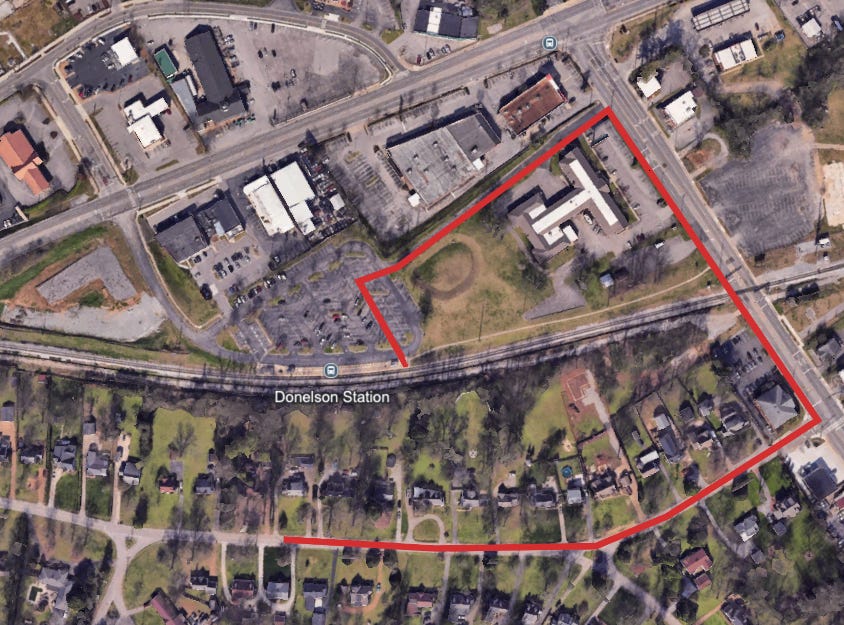

Pedestrian connectivity is another glaring issue. The more accessible and porous a train station is, the more usable it becomes. But at Donelson Station, for example, there is only one entrance on one side of the station. This means that a house directly next to the train station still requires a 0.6-mile walk just to reach the platform. Proximity means nothing if the station is inaccessible.

What Good Regional Rail Needs:

Porous, well-connected stations that prioritize accessibility for pedestrians.

Ample bus and rail connections to provide reliable first/last-mile transit options.

3. It Is Not Frequent at All

The service operates only three trains during the morning peak and three during the evening peak in both directions, with no weekend service. To put that into perspective, the Long Island Rail Road’s Babylon Branch runs 74 trains in each direction on weekdays alone.

By limiting service to rush hour, the train effectively restricts its own usefulness. Riders have no expectation of using it outside of that window, even though its final stop is on a street with one of the highest concentrations of nightlife in the country.

If a transit system doesn’t allow you the freedom to change your plans, leave when you want, or get to work without fear of missing your train, it’s not a real alternative to driving—it’s a constraint. Frequency is freedom.

What Good Regional Rail Needs:

Service every 20–30 minutes (or better), all day, seven days a week.

4. It’s not part of a network

A single rail line with few or no connections has a harder chance of success. Without an integrated network, the only way it can be useful is if both the origin and destination are within a quarter- to half-mile of the rail line—a highly unrealistic expectation.

The original vision for the system included six radial lines, connecting each satellite city to downtown Nashville. However, since CSX owns routes 2–6, only the Lebanon route (1) was chosen, effectively isolating the service.

A true regional rail system would allow people to take a train not just to downtown Nashville, but also between satellite and tertiary cities within the Nashville-Davidson metro. Additionally, there is no intercity rail within the state or to neighboring cities that could help unify a regional network into a hierarchical system, incorporating high-speed rail and urban transit.

For comparison, Munich’s S-Bahn serves a metro area three times the size of Nashville, yet its seamless connectivity allows trains to run through the urban core while linking to other rail networks across multiple levels of service. That’s how a real regional rail system works.

What Good Regional Rail Needs:

A comprehensive rail system that connects major population and employment centers across a region.

Fare integration that allows seamless transfers between train lines and other transit modes.

5. It is Not Fast

Step into any New York City subway car, and you'll see a mix of people from all walks of life. Recently, I saw a woman on the L train, wearing a fur coat, sunglasses, and $800 Louboutin shoes. She could easily afford a private car or an Uber, but she still chose the L train—because it’s faster than any car along the same route at rush hour.

Riders will always respond to convenience and speed when given real choices.

The WeGo Star’s fleet consists of 45-year-old diesel-powered EMD F40PH locomotives, which are far heavier than modern electric multiple units (EMUs). This weight difference makes them slower to accelerate and decelerate at stations. In contrast, Caltrain improved speeds by 20% simply by electrifying.

Between infrequent service, outdated trains, and a lack of transit connections, nearly every possible trip on this route is slower than driving or taking a rideshare. And if transit can’t compete on speed, people won’t use it.

What Good Regional Rail Needs:

Regional rail needs to be electrified and grade-separated whenever possible to minimize conflicts with cars, improve speed, reliability, and increase speed.

It’s Actually Good That This Train Isn’t Successful

You may have noticed that I’ve used the aspirational term "regional rail" instead of "commuter rail", which is how the WeGo Star is officially classified. The difference is in the name—commuter rail is designed exclusively around the 9-to-5 work commute, which is why the WeGo Star has no weekend service, no midday or evening trains, and no connections outside of downtown Nashville.

As I mentioned earlier, this rail line was never designed for success. It was born out of a lack of political will, minimal investment, and zero ambition for real transformative transit—all on an insanely small budget. When transit is set up to fail, it’s not surprising when it does. And that failure reinforces what transit advocates already know: the core principles that make rail successful are universal and non-negotiable.

Every trip a person takes is a choice between competing transportation options. If the train is faster and the music venue has no parking, people will take the train. If someone is just going down the street to a corner store, they’ll probably walk. But in the suburbs of Nashville, where the WeGo Star offers just six round trips per day and virtually no reliable fixed-route transit connections, it’s no surprise that almost no one finds it useful.

When Nashville voters passed the transit and infrastructure investment referendum last November, they sent a clear message: they want a better transit future. Now, it’s time to deliver on that vision.

Source: https://www.progressiverailroading.com/passenger_rail/article/Nashvilles-Music-City-Star-Commuter-rail-on-a-budget--13215

I ride this train daily from Hermitage and definitely agree with the issues presented here. I can also speak to the questions posed in section 2:

1. (Why not the bus?) The bus is subject to the same traffic as everyone else. Coming back it can easily take over an hour while the train is consistent both ways.

2. (Why not drive?) Traffic applies here too, but also parking costs in downtown are insane. Many employers do not provide free parking and there may not be capacity for everyone to park there.

That’s part of what makes the train situation so frustrating. The train is (for me) genuinely a better experience but that’s more because of how bad all the rest of the infrastructure is here. And that’s also because I specifically chose to live in a location that would make it viable. It’s so bad that even a merely so-so system would be a huge improvement.

I think the foremost issue Nashville needs to solve is the first and last mile connectivity. I could not walk to the station unless I want to spend half of that time on the edge of a busy road with no sidewalk. There are bus stops that are literally on the shoulder of a 50mph road. We have so far to go but at least we are seeing steps.