How to Build An Actually Great Rail System in Delaware

The Case for a Swiss-like Rail System in Delaware

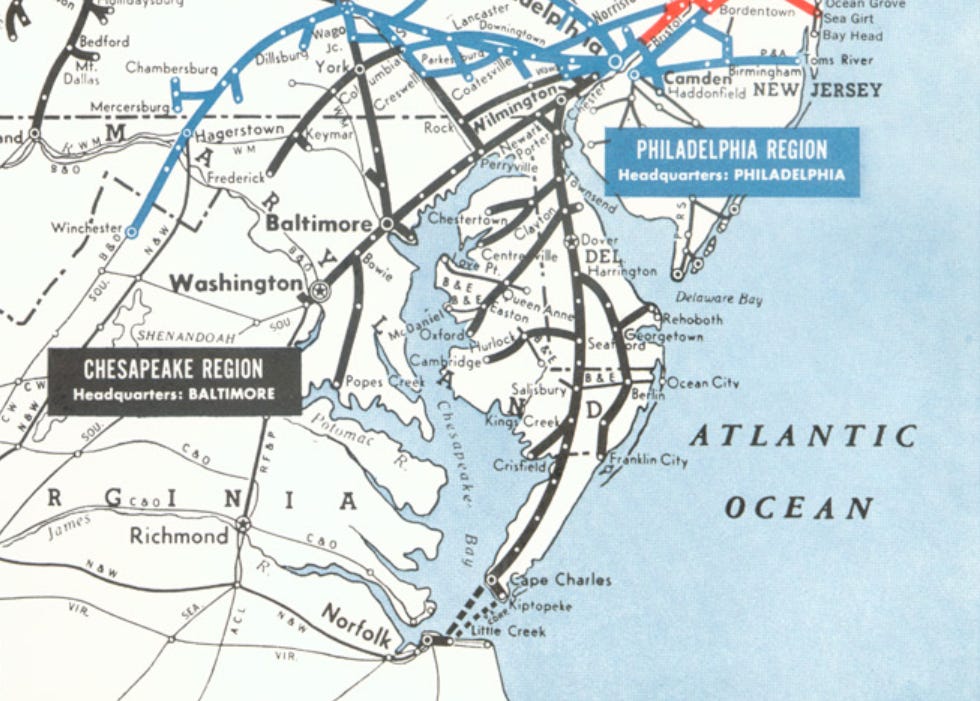

America once had the greatest rail system the world had ever seen. From tiny towns in South Dakota to mid-sized cities in Ohio to the biggest urban centers, trains stitched the country together. Even small towns in southern Delaware weren’t left out. They might only see a handful of trains each day, but those trains connected them into the larger Penn Central network, and from there, across the entire Eastern Seaboard.

Today, almost all of that is gone. Outside the Northeast Corridor, what’s left are a few mainlines through major cities, with maybe one, or if you’re lucky, a few Amtrak trains stopping each day. The idea of rail service linking small town to small town has all but disappeared, dismissed as too expensive and too politically toxic to revive.

But what if I told you the tracks are still there, underutilized, intact, and that they could reconnect nearly every major population center in Delaware with just two lines?

Welcome to Delaware’s forgotten rail network.

Once home to the Delaware Railroad, later absorbed into the mighty Penn Central, this state was once served by trains to nearly every city and town, including those on the Maryland peninsula.

What’s left

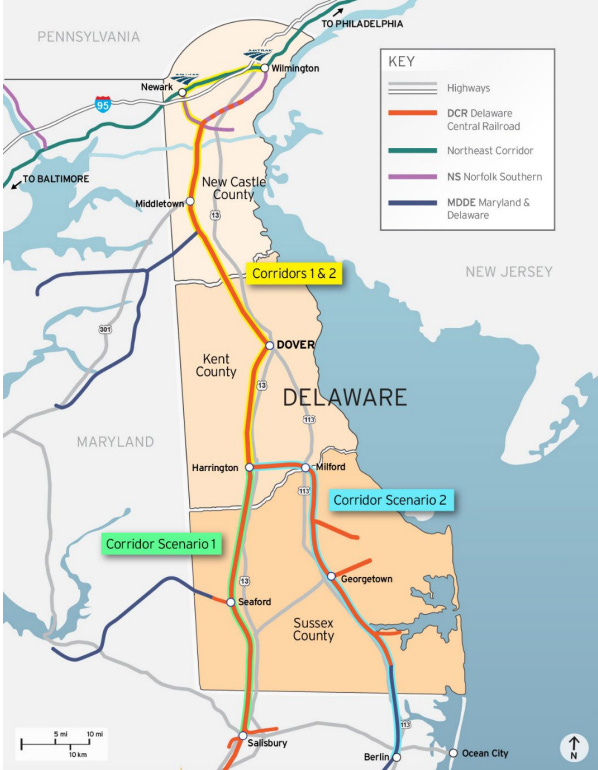

Much of that infrastructure still exists today, even if no passenger trains run outside the Northeast Corridor. The tracks are in decent condition, anchored by two north–south corridors: the Delmarva Secondary and the Indian River Secondary.

Together, these corridors already cover most of the state. With smart upgrades and feeder bus connections, they could form the backbone of a statewide rail network, no new right-of-way required.

So let’s get into it.

My Delaware Rail Proposal

I’m not here to argue whether Delaware should have intrastate rail. To me, the answer is obvious: in the second-smallest state in the country, with well-defined corridors and relatively little downstate sprawl, rail just makes sense. The question isn’t if, it’s how.

My Assumptions

Use the existing right-of-way (ROW) to avoid endless NIMBY fights and eminent domain battles.

Stick within the FRA (Federal Railroad Administration) guidelines to keep the plan realistic.

Propose something that’s technically sound, economically viable, and politically feasible.

Here’s why this matters: Delaware already has two north–south rail corridors that directly connect about 20% of the state’s population (municipalities along the lines). The state is currently studying a “no-frills” commuter rail model, slow, infrequent, and uninspiring. Frankly, Delaware deserves better.

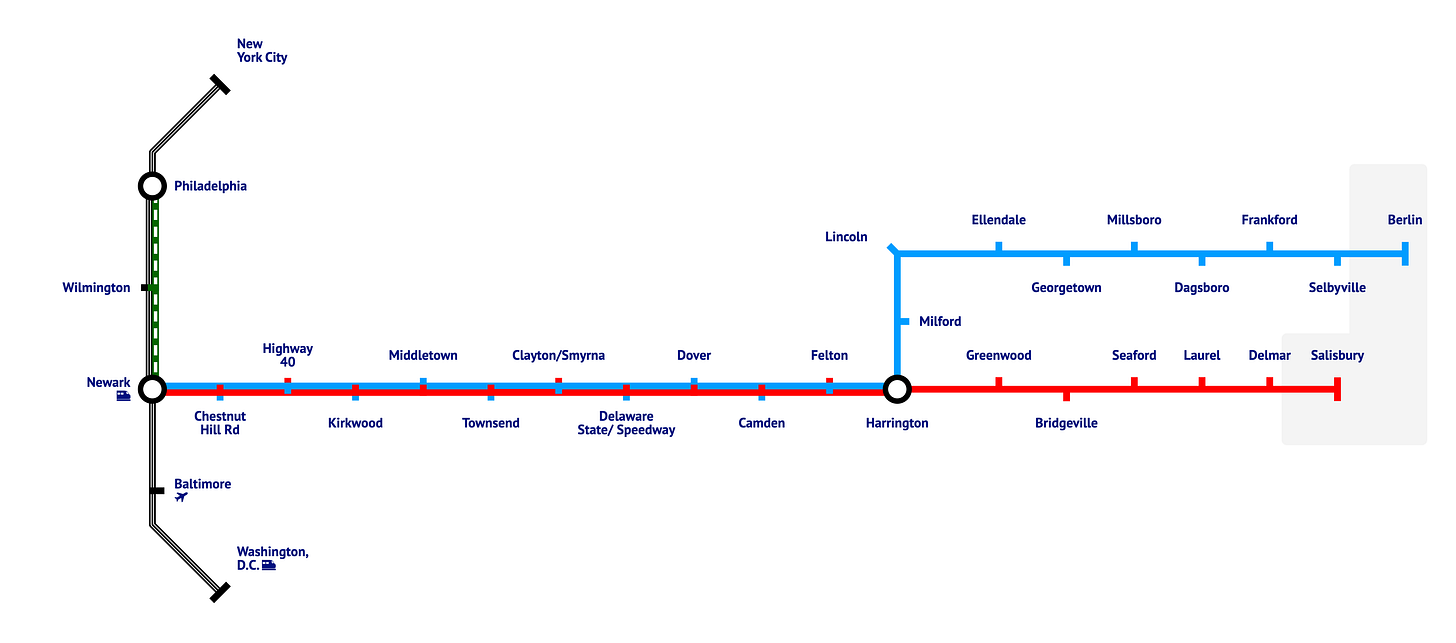

For this proposal, I’m imagining two routes (as being studied above):

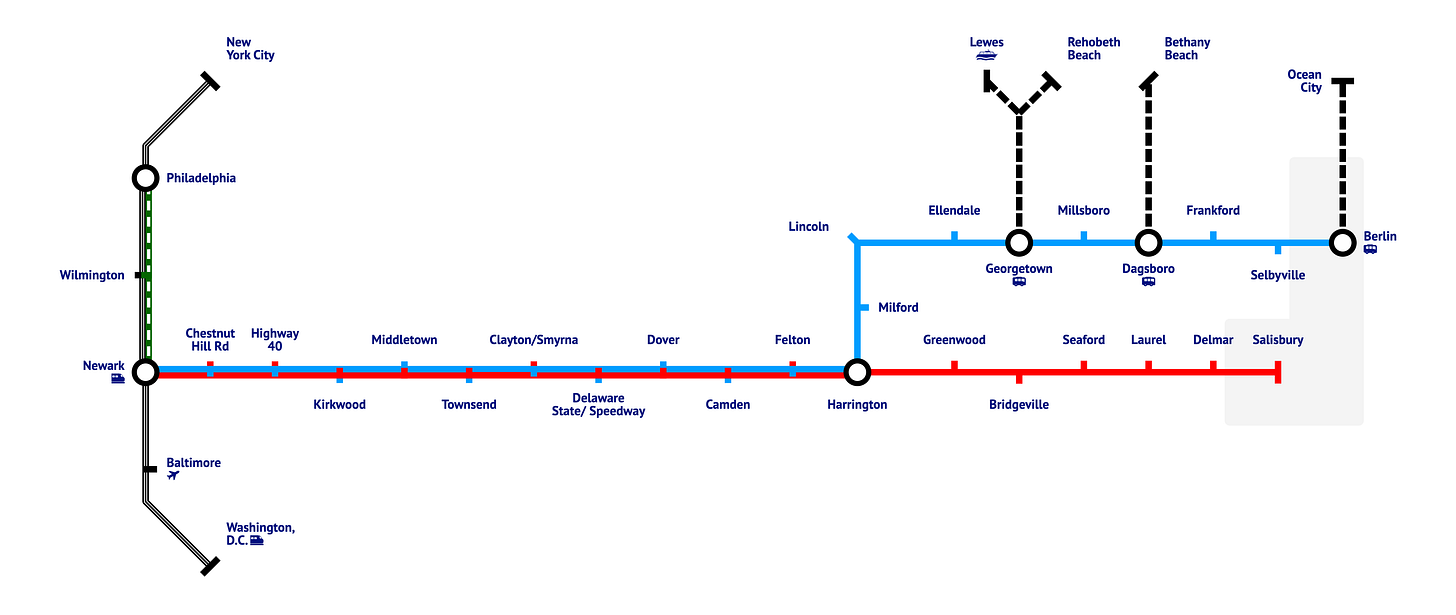

The Berlin Line (Newark to Berlin)

The Salisbury Line (Newark to Salisbury)

Type of Train:

Right now, the state is studying “no-build” options, essentially starting service with minimal investment. That likely means slow, heavy diesel trains pulling around old passenger cars recycled from other agencies. Functional, sure. Inspiring? Not at all.

Delaware deserves better.

I propose a four-car Stadler KISS EMU (or a similar FRA-compliant electric train). Right-sized for downstate communities, modern, and efficient.

Why electric? One word: torque. Electric trains are lighter and can deliver maximum torque (rotational force) instantly, while diesel engines take time to spool up. Just look at Caltrain’s transformation when they switched from diesel to electrified sets, the difference is night and day. Check out the difference with Caltrain:

I know some people will push back and say I should consider diesel sets for realism. And I’m open to doing that analysis if enough readers want it. But in 2025, we should be planning electrified rail systems, not clinging to diesel.

So let’s go with a four-car bi-level Stadler KISS, which can carry up to 880 people at full capacity (configurations/capacity are fully customized so tbd).

The Routing

Newark makes the most sense as the northern terminus, since it already connects to SEPTA and Amtrak. Extending further into Wilmington would require adding tracks to the Northeast Corridor and reconfiguring Wilmington Station, something I don’t yet have the freight data to analyze. For now, Newark is the logical (and feasible) endpoint.

That said, I know this leaves Wilmington and New Castle underserved. That’s a big gap, and one I’d like to explore in more depth in a future piece.

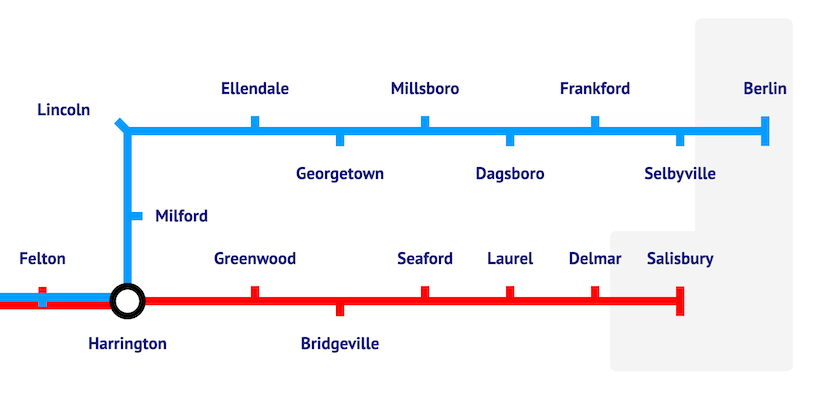

From Newark, trains would follow the Delmarva Secondary line south to Harrington, where the route splits into two branches (Blue and Red Lines). Along the way, 28 stations would serve substantial communities with intact urban cores, places that already lend themselves to rail thanks to walkability and solid last-mile potential.

Frequency and Span

Service would run every 30 minutes, from 5 AM to midnight, with no need for peak-only boosts. For context: Seaford, DE, a town of about 9,000, would see a train in each direction every half-hour. That’s close to Swiss-level service.

Speeds

This is the most important piece. With the infrastructure upgrades I outline below, I’m conservatively assuming a max speed of 79 mph. Realistically, it could reach 90–110 mph, but I’ll stay conservative here to avoid overpromising.

Inputs for calculations:

Top speed (Vmax) = 79 mph (≈ 35.3 m/s)

Acceleration (a) = 1.1 m/s²

Braking (d) = 1.0 m/s²

Station dwell = 30 s (with high-level platforms)

Using these assumptions and factoring in the distances between stations, the results are clear: the train beats driving at every segment simulated. READ THIS AGAIN.

Berlin Line → 105 minutes

Salisbury Line → 93 minutes

One odd quirk: previous state rail studies required “quad gates” (four-gate crossing protection) which are required for speeds up to 110 mph, but then set the intended speed well below that. If we’re building to that standard anyway, why not take advantage of it? For now, though, I’ll stick with the conservative 79 mph estimate.

(If you want to check station-to-station travel times, I’ve uploaded the full dataset: LINK)

Infrastructure Upgrades

Tracks:

The entire right-of-way (ROW) is currently single track, which creates scheduling headaches. With 30-minute all-day headways, conflicts north of Harrington (where the two routes interline on the same track) become unavoidable.

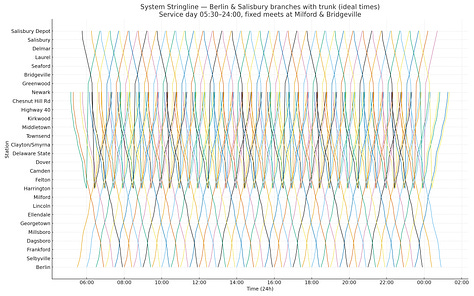

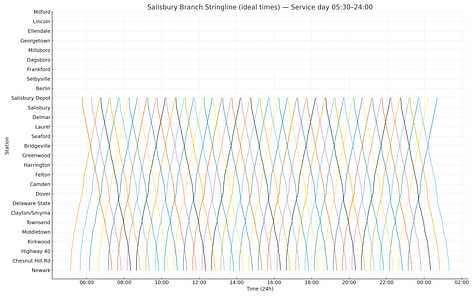

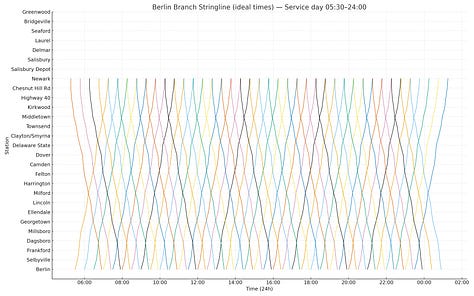

(Quick note: if you’re not familiar with train stringline diagrams, each line represents a train trip, showing time on the x-axis and station location on the y-axis. They’re a great way to visualize where conflicts or bottlenecks occur.)

To “rip the Band-Aid off,” here’s what’s needed:

Double track from Harrington to Newark → 60 new miles.

Passing sidings → 1 mile each at Milford and Bridgeville to allow overtakes and scheduling flexibility.

Track renewal → 149 miles of refreshed track (ballast, ties, regrading, fixing track geometry).

Grade crossings → upgrade all 171 crossings to modern standards.

Electrification → 208 miles of overhead wire to enable modern, high-torque electric service.

Stations:

One of Delaware’s hidden advantages: nearly every community along these lines already has a logical spot for a station. Many towns have intact urban cores, walkable streets, and available land near the ROW. That makes station placement straightforward compared to larger metro projects.

All stations should feature:

High-level platforms → faster, accessible boarding and shorter dwell times.

ADA access via ramps → avoiding costly elevators/escalators wherever possible.

Basic amenities → shelter, benches, good lighting, countdown clocks, and wayfinding signage.

What’s needed:

16 single-platform stations (for the branch lines).

12 two-platform stations (for the trunk line).

One new platform at Newark → to handle SEPTA/Amtrak connections and reduce conflicts with existing service.

The design should lean utilitarian, not flashy: durable, easy to maintain, and built to make passenger flow smooth.

Right of Way/Freight Traffic:

The good news: eminent domain would be minimal, if necessary at all. Most of the proposed stations sit on or adjacent to land already controlled by the rail operator.

As for freight, traffic on these lines is relatively low. That makes passenger service technically feasible without massive conflicts. In fact, it strengthens the case for Delaware to purchase the corridor outright. Owning the ROW would allow the state to prioritize passenger trains while leasing trackage rights back to the short line and freight operators who still use it today.

Why does this matter? Because pouring money into upgrades on tracks you don’t control is a recipe for frustration. Passenger rail needs reliability and scheduling certainty, and that only comes when the public controls the corridor.

Cost:

(Estimates come from both the Delaware State Rail Plan and my own calculations, based on North American comparisons adjusted for the state’s cost of living)

Operational Cost:

Operating costs are difficult to benchmark, but using New Jersey commuter rail ($708/revenue hour) as a baseline and adjusting for Delaware’s transit operating cost (~$500/hour), a system providing 242 daily revenue hours year-round would cost roughly $44.2 million annually.

Where this system lacks

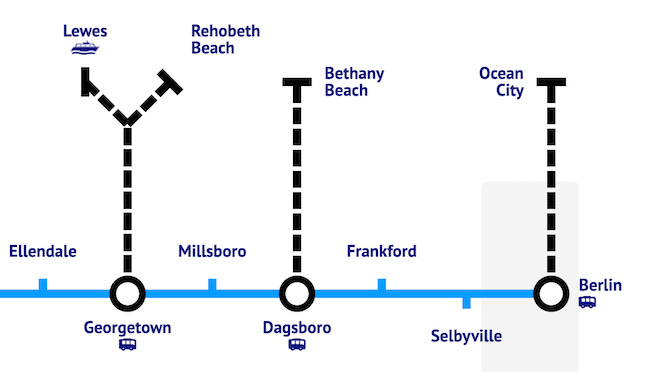

Delaware’s identity is tied to its beaches; Rehoboth, Bethany, and Ocean City, MD are major draws. These places were once connected by rail, but those rights-of-way are long gone or converted into rail-trails. Bringing trains back there simply isn’t politically or practically feasible today (ugh).

That said, the rail system I’m proposing can still serve as the backbone. Timed local buses or shuttles connecting directly to the half-hourly trains would make the beaches accessible without needing a car. It’s not as seamless as rail, but it’s realistic.

And yes, I’d love to someday revisit the idea of restoring direct rail or even rapid transit to the coast. If that’s something you want to see me explore in detail, let me know, it’s a conversation worth having.

Where this proposal lacks

One gap I haven’t fully explored is the Wilmington–NEC corridor. Ideally, some trips could run directly to Philadelphia rather than stopping at Newark, but I don’t yet have the data on freight traffic or the track configuration to make a solid case. That’s something I’d like to dig into in a future piece.

Another challenge is the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal Lift Bridge. It’s single-tracked, in desperate need of refurbishment, and will need major investment regardless of passenger service. The question is: does this project trigger that rebuild, or do we think bigger? A 1.16-mile tunnel at a 2.5% grade is technically feasible and would avoid the movable span entirely. Alternatively, a 1.2-mile viaduct on either side of the canal could replace the lift bridge. Both options are costly, but they’d future-proof the corridor.

Just Imagine

Picture this: a Delaware rail system that reliably connects every corner of the state, and is faster than driving almost everywhere.

You’re dreading parking at the Delaware Speedway, so you stroll down to the Seaford station. A sleek train pulls in right on schedule, and 37 minutes later you’re at the track with friends. Or you’re headed to Dover to advocate at the state capital, and instead of a stressful drive, you hop on a train that runs every 30 minutes. The beach, dinner with family, class across the state, all just a train ride away.

This isn’t fantasy. It’s entirely feasible with existing technology, and it’s been achieved in countries with smaller economies than ours. If Delaware is going to wait a decade for a slow, uninspiring commuter rail line, why not aim higher?

Let’s build something that takes us into the future instead of leaving us saying “that’s it?”

Is there a software you used for these calculations or did you do them freehand? Where do you access freight rail data?

I think this is excellent work, as someone who’s born and raised in Delaware.

You mentioned you’d like to circle back to a piece about Wilmington and New Castle. I’d personally love to see an article about a Light Rail system that runs along the median of route 40 from the Wilmington Transportation center (Amtrak Station) connecting to DCR / NS just south of the route 40 / 13 split. Perhaps this was already the alignment you had in mind?

Not only would this 7-mile section connect your line to Delaware’s most populous city (terminating at Amtrak’s northeast corridor) but it would also finally create rail connection to Delaware’s sole commercial airport. Going north from the Wilmington train station there could also be a phase 2 expansion that occupies the median of route 202 up to the Pennsylvania state line by way of Walnut street and concord ave. Both the route 13 corridor and the route 202 corridor have ample opportunity for transit oriented development, filled with fledgling strip malls and parking lots.

Even if there are no new lines constructed, I think the state of Delaware could invest more heavily on the NEC itself. Instead of relying on SEPTA’s rolling stock, DART could purchase its own trains running exclusively between Newark and Claymont. There’s definitely room for more stations with transit oriented development at Newport, Stanton, Ogletown, Bellefonte, and Holly Oak.

Our state is expecting population growth for the next 30 years and these types of projects need to be part of that discussion.