(While all the scanned memos and reports I reference come from Nixon’s library and government archives, I accessed them through the historical document archive at the Eno Center for Transportation, thanks to the incredible work of Jeff Davis.)

The Decline of Passenger Rail

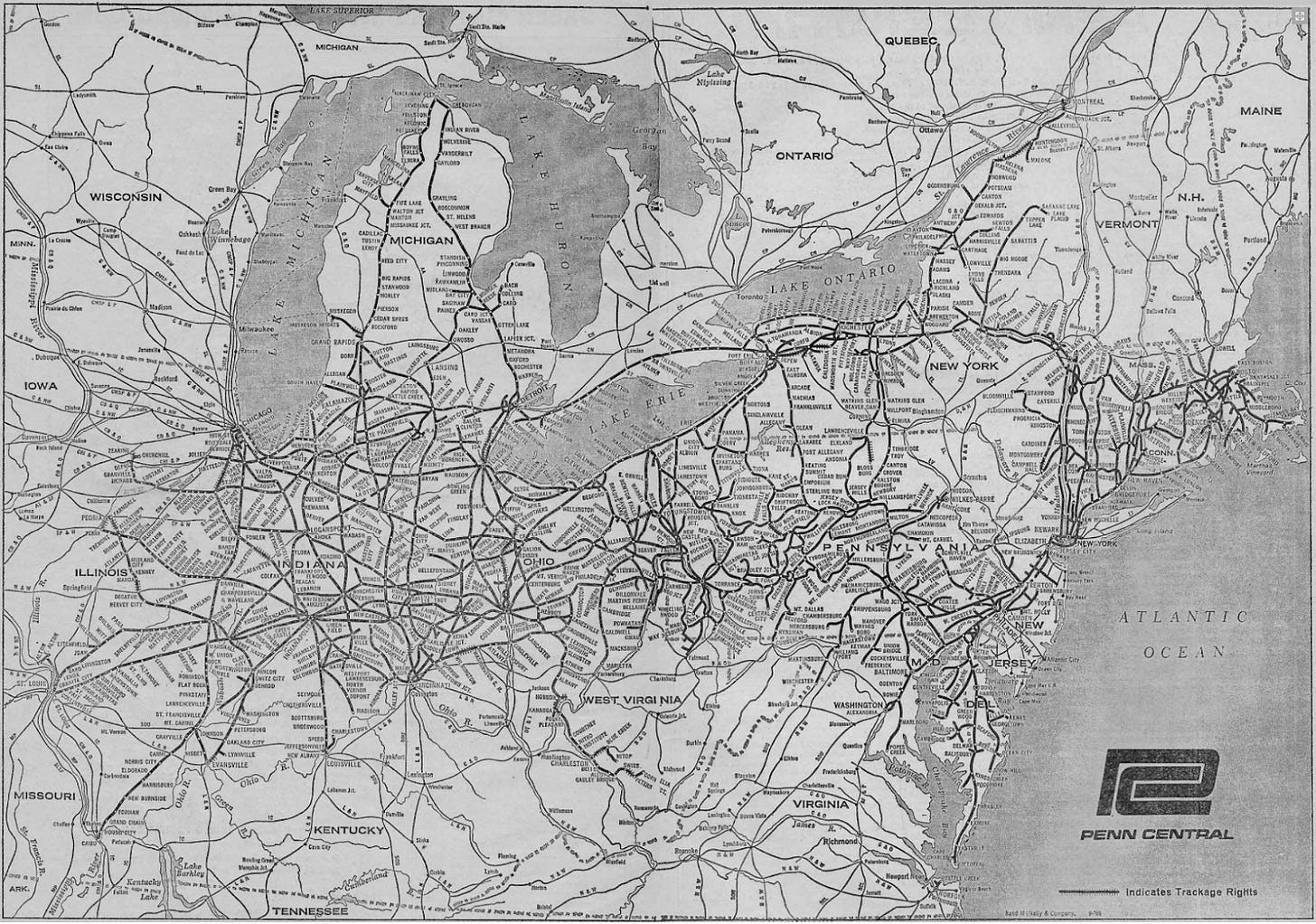

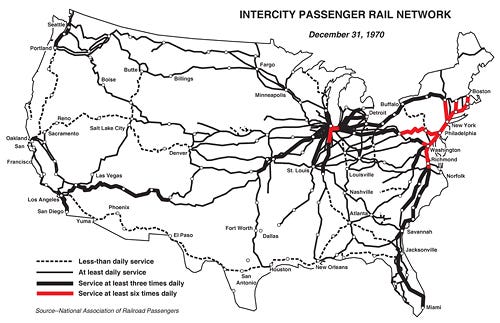

It’s 1969, and the once-bustling halls of Kansas City’s magnificent Union Station now stand eerily quiet. Just a few decades earlier, the station served over 200 trains daily; now, it struggles to see even eighteen.1 Penn Central, the newly formed company merging the Pennsylvania and New York Central Railroads, was the largest eastern passenger rail operator—but it is already in dire financial straits, soon to file what would become the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history. The golden age of passenger rail lies in ruins, eclipsed by the rapid rise of air travel, widespread car ownership, and the relentless march of suburban sprawl.

Only 500 passenger trains remain in operation across the United States—just 50% of the number from the previous decade and a mere 2.5% of the service seen in earlier decades. The private passenger rail market, once thriving, has been in steep decline since World War II, now suffering a staggering $200 million annual loss (equivalent to $1.77 billion in 2025). USPS mail, once transported on 10,000 trains daily and provided a critical revenue stream that kept passenger rail afloat, had also become virtually nonexistent.2 Without intervention, the country’s once-proud passenger rail system was at risk of “disappearing completely.”

Yet, amid this grim outlook, one corridor offered a glimmer of hope.

The Metroliner: A Glimmer of Hope

The Metroliner, the predecessor of today’s Acela, was conceived under the Johnson Administration through the High Speed Ground Transportation Act of 1965 and launched in 1969. Operated by Penn Central, the Metroliner was a high-speed rail service reaching speeds of 110 mph between New York City and Washington, D.C. Its success was undeniable: it stunted air travel growth along the corridor, where annual increases of 15% dropped to just 0.4%, and the route even turned a profit.3 Reflecting on the Metroliner, Department of Transportation (DOT) Secretary John Volpe stated:

“The successful rail passenger service offered by the Metroliner operating between New York and Washington has demonstrated that given fast, clean, safe, comfortable and convenient service, a significant segment of the public will chose rail travel as a preferable mode of intercity travel.”

Despite the Metroliner’s success, not everyone agreed that saving passenger rail was a worthwhile endeavor. The Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 (known as “Railpax”), which aimed to create a for-profit national passenger rail corporation in an industry on the verge of collapse, garnered strong bipartisan support in Congress. However, skepticism loomed within the White House. Domestic policy chief John Ehrlichman dismissed trains as an “uneconomic mode,” reflecting President Nixon’s mixed feelings about the proposal. Despite these reservations, “strong political pressure” from the public and Secretary Volpe’s firm support made resistance difficult. In his memo to Nixon, policy advisor Peter Flanigan cautioned:

“Therefore, unless the President is prepared to risk Secretary Volpe’s resignation, I would recommend that he signs the Railpax bill.” - October 27, 1970

President Nixon signed the Rail Passenger Service Act into law on October 30, 1970, giving the government just six months for the new rail corporation to operate service (the law required Railpax be operational for May of 1971). Railpax would handle schedules, train procurement, marketing, and reservations, while operations and maintenance would remain with the private rail companies.

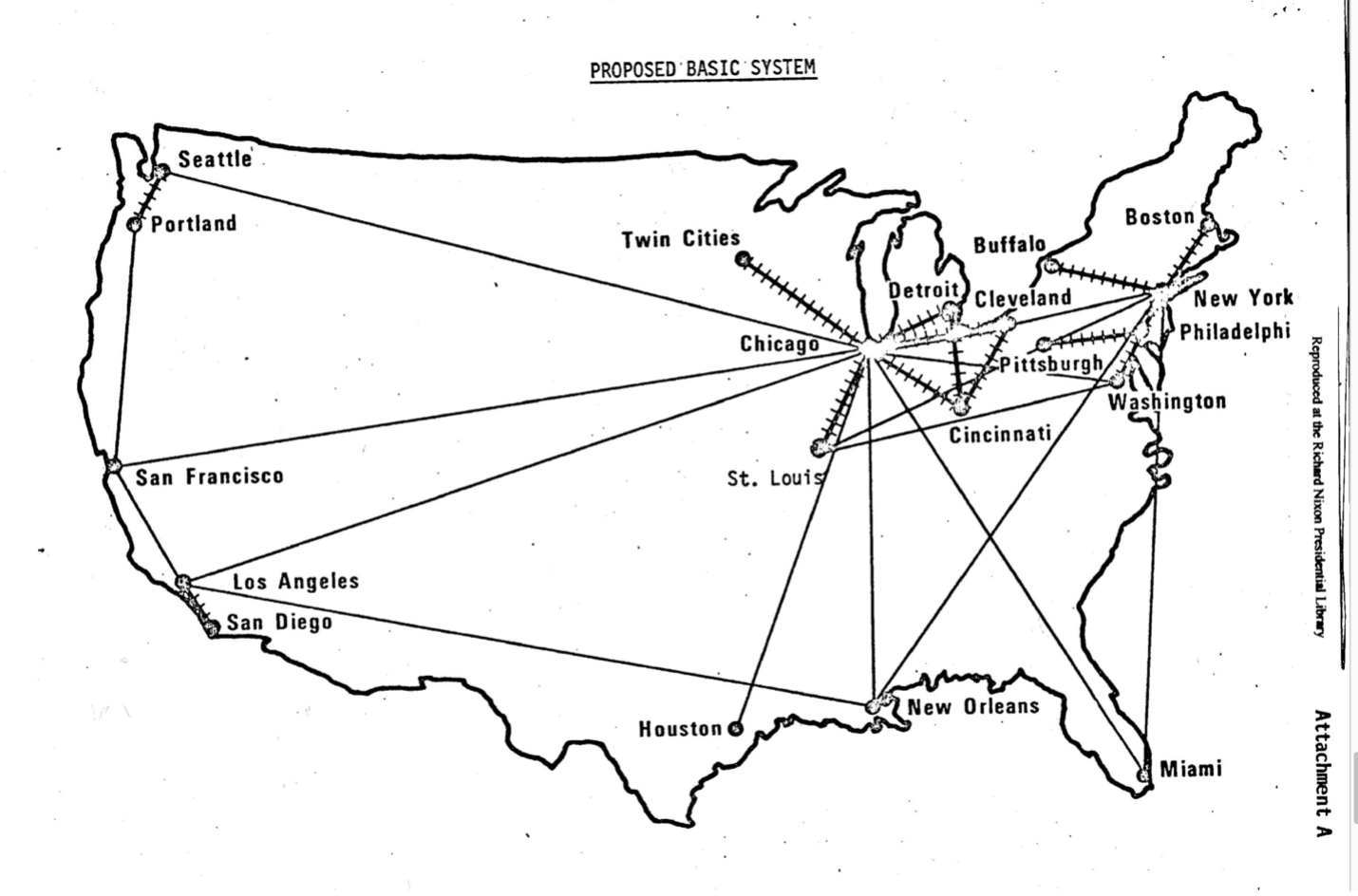

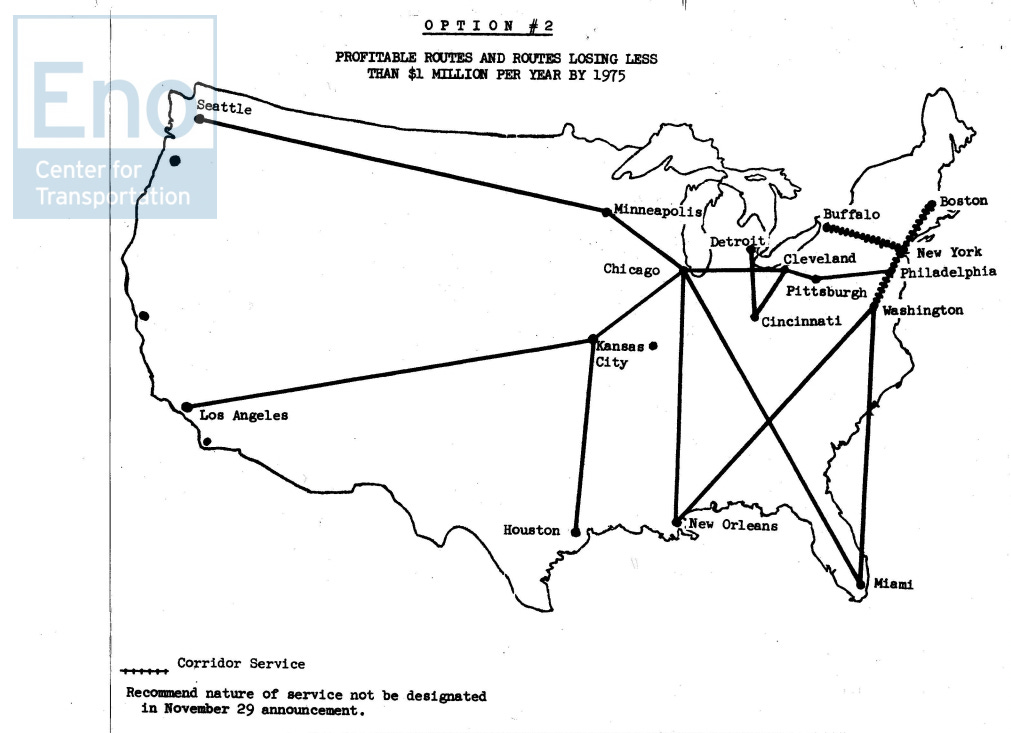

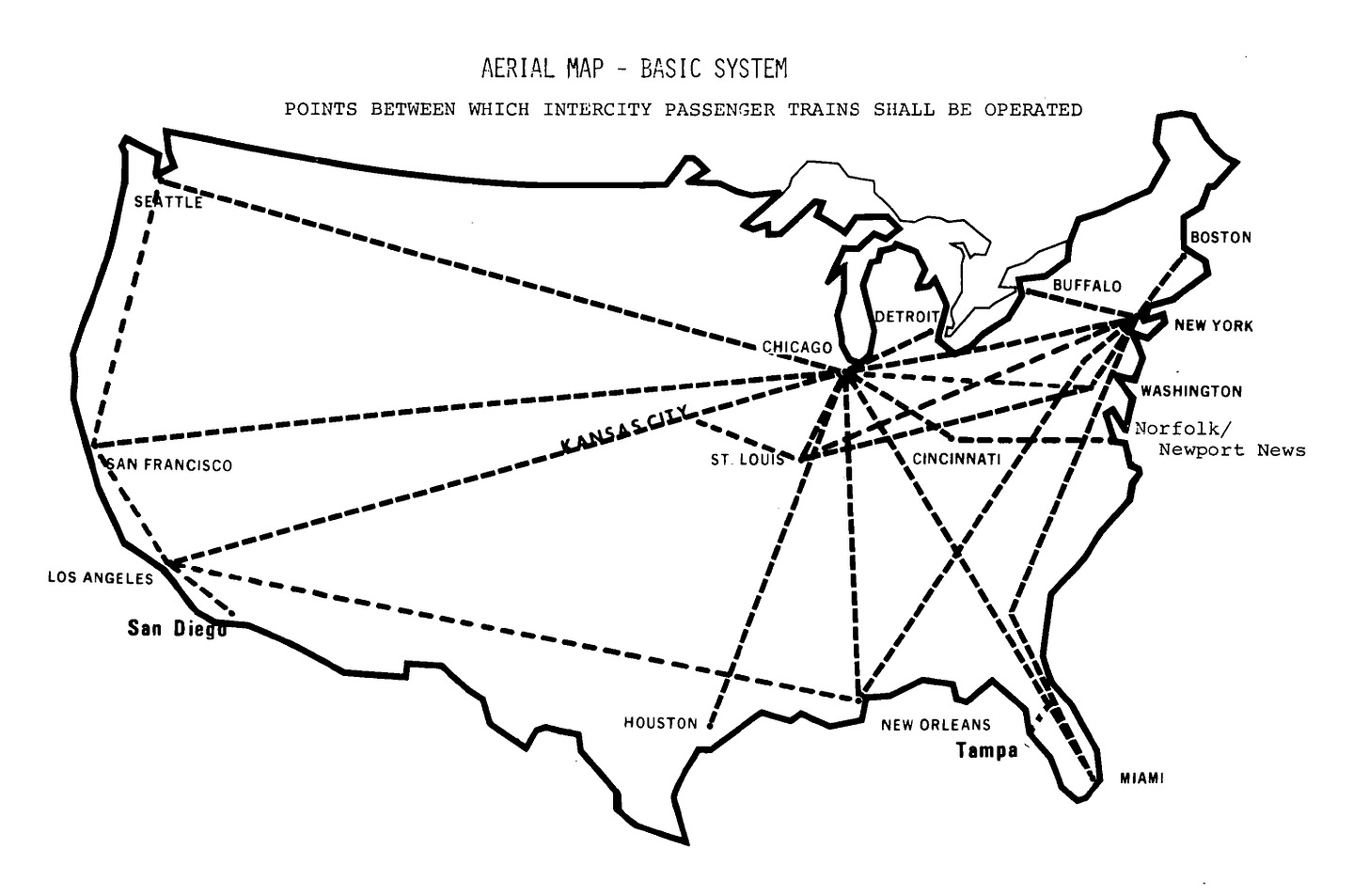

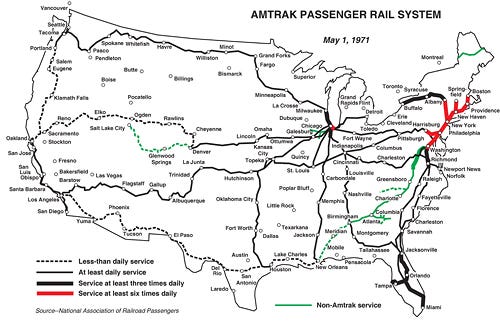

The following month, Secretary Volpe sent a preliminary report to President Nixon outlining a proposed “bare bones” system map with just 27 routes, including 14 classified as “long haul” (above map). The decline in service was staggering: long-haul routes were reduced by 73%, with only 14 trains remaining in operation compared to 142 in service at the time. While the Rail Passenger Service Act was meant to save passenger rail, its initial implementation would come at the cost of drastic service reductions, reflecting the difficult balance between financial viability and maintaining a national network.

The OMB Proposal (November 1970)

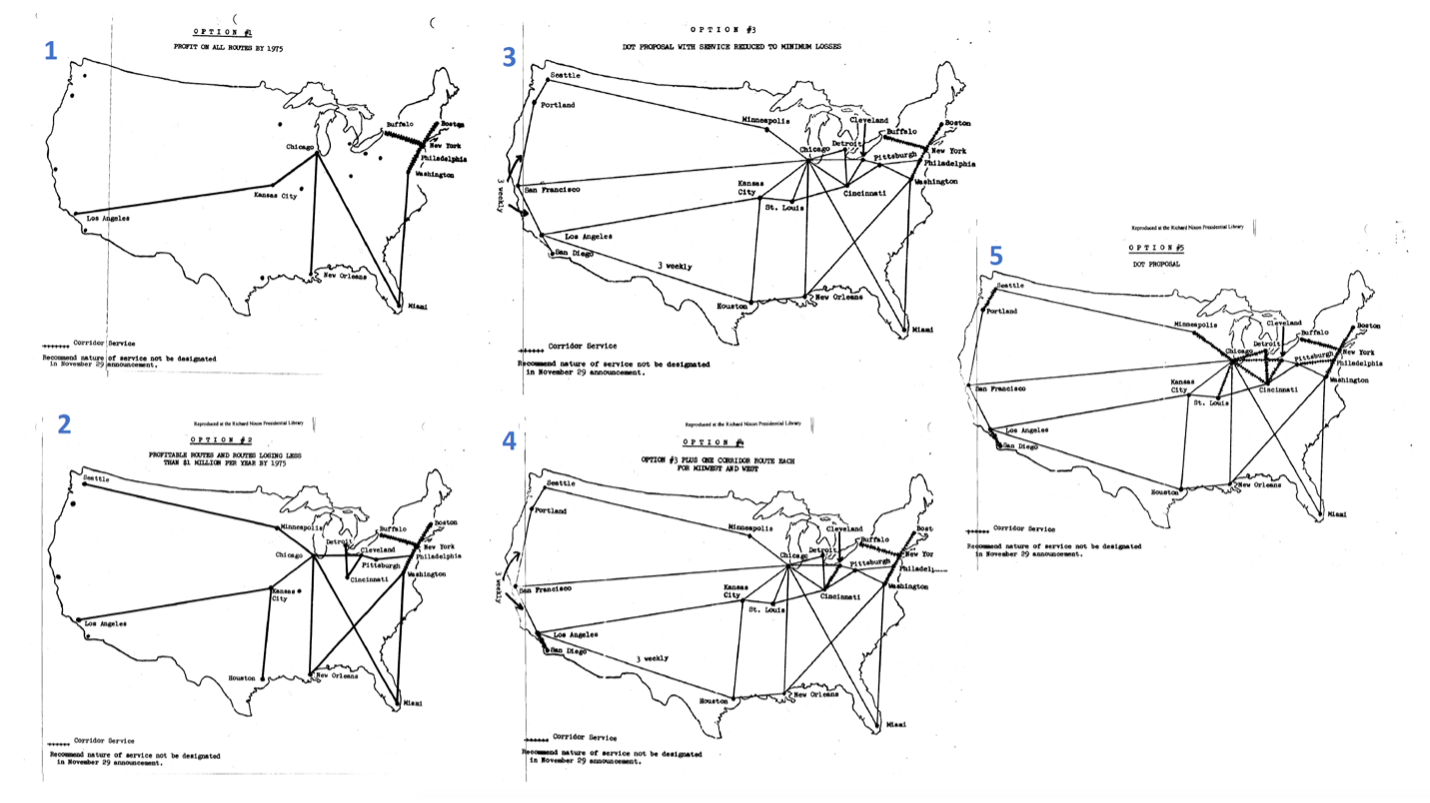

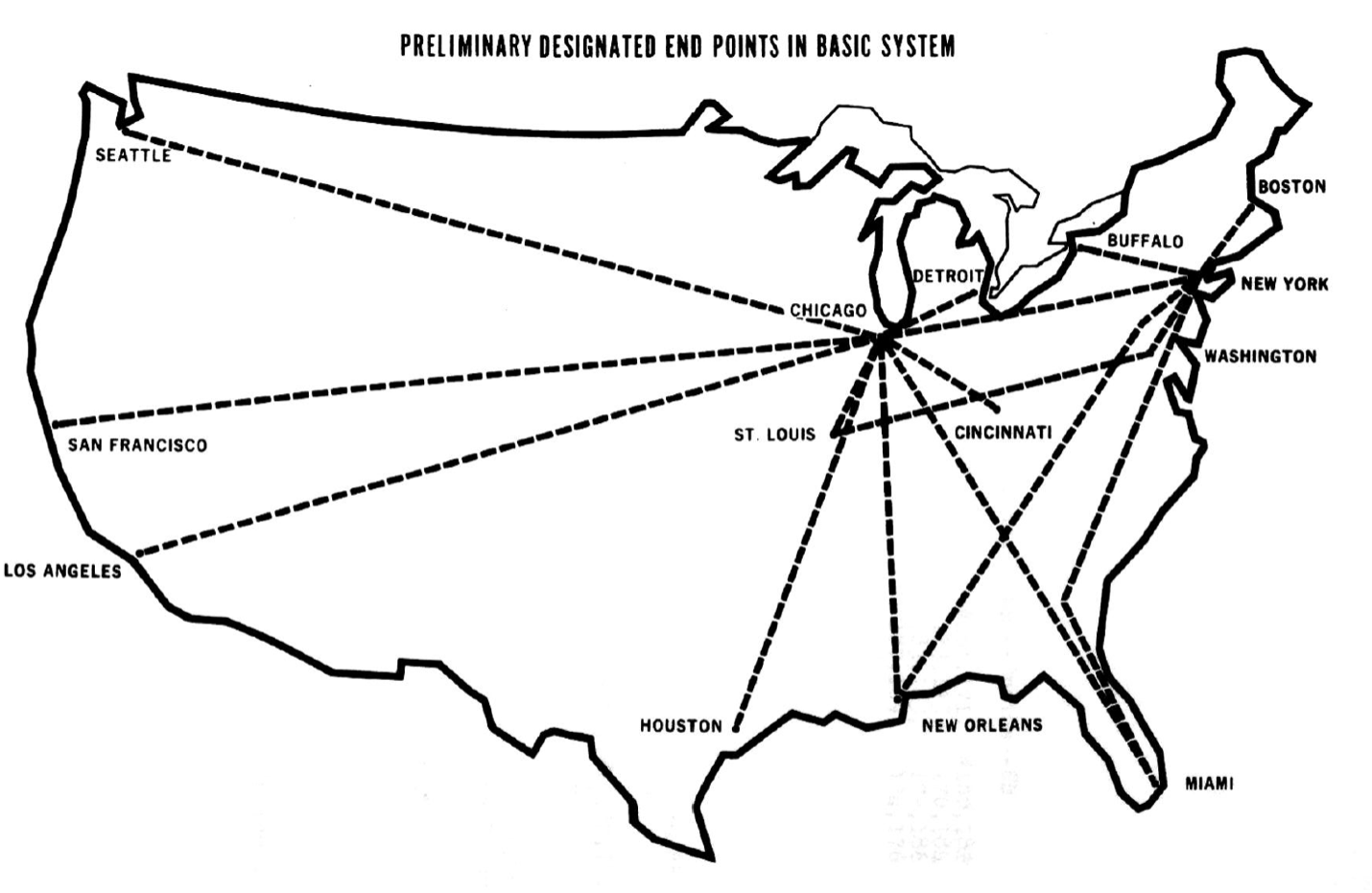

Within 48 hours of Secretary Volpe’s DOT proposal, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), led by Director George Shultz, released its own set of five proposed systems for President Nixon to consider. Unlike the DOT’s more ambitious vision, Shultz and the OMB believed Volpe’s proposal was overly “extensive” and financially risky. To begin with, it should be noted that the agency was quite outspoken about not saving rail.

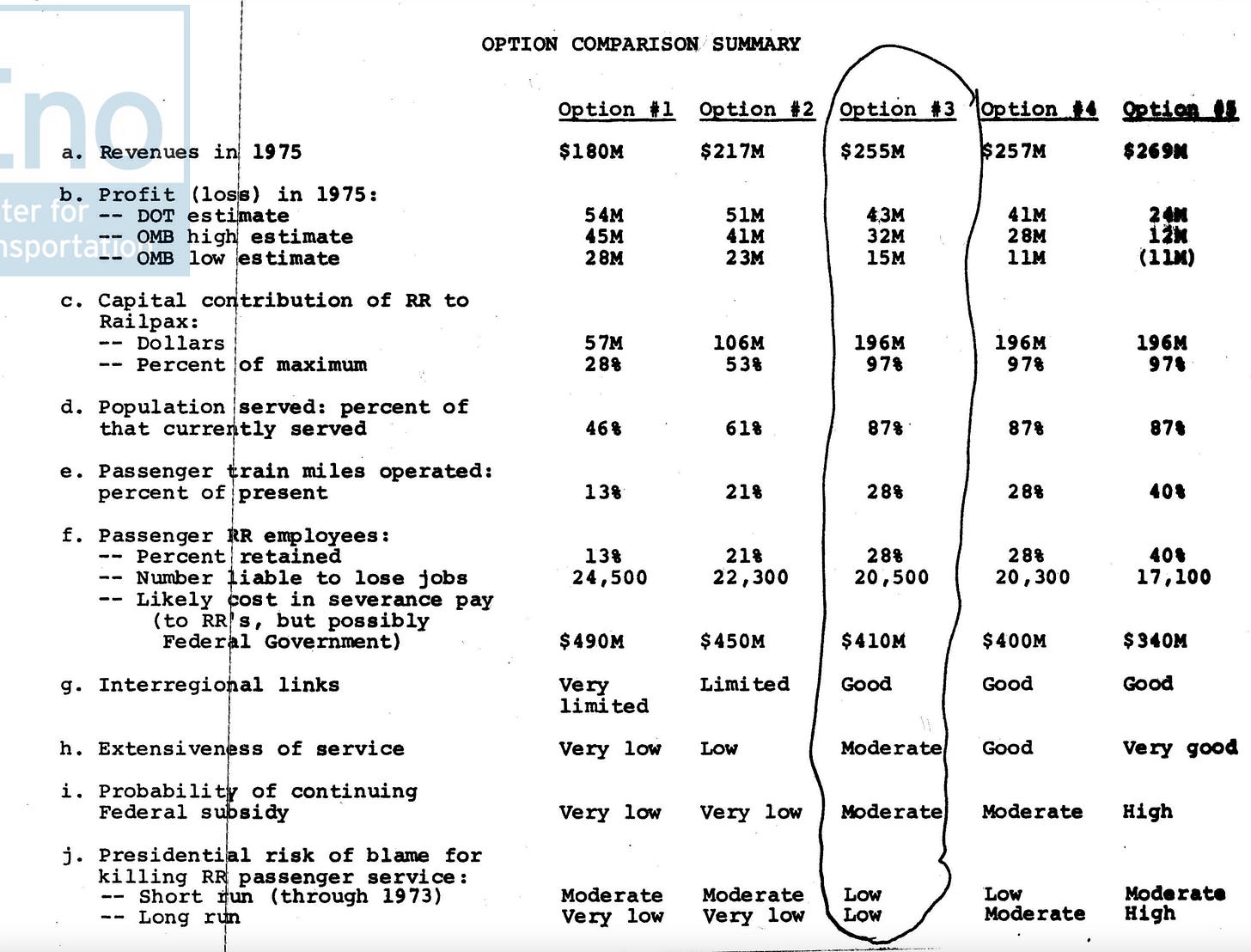

The five OMB options ranged from a “profit-maximizing” system (#1) to a “service-maximizing” system (#5), which mirrored the DOT’s recommendation.

Interestingly, the memo from Shultz, now preserved in Nixon’s Library, lacks a clear recommendation and left blank. Analysts at the Eno Center for Transportation suggest that OMB likely leaned toward either Option #2 or Option #3, as they addressed key concerns raised by Shultz’s agency (option #3 was circled).

These concerns outlined included:

Limited financial margin for error due to overly optimistic revenue projections.

The likelihood that numerous routes would remain unprofitable by 1975.

Increased risk of a federal subsidy beyond the initial funding allocation.

The potential for significant political fallout, including blame for the corporation’s failure, the demise of national rail service, and possible nationalization of the railroads.

After reviewing OMB’s very cautious recommendations, Nixon faced a difficult choice: balance public and political expectations for a robust rail network with the fiscal concerns raised by his advisors.

Nixon’s Choice

A month later, Secretary Volpe received a memo from Director Shultz, written on President Nixon’s behalf, announcing that the President had chosen OMB’s Option #2 plan. This option offered the second-lowest level of train service among the proposals but was also the second most likely to achieve profitability, but would result in 22,300 rail jobs lost.

To manage public expectations, the administration imposed strict conditions for the announcement, which was scheduled for November 30, 1970. These conditions included:

Only the endpoints of the routes (shown below) would be announced; intermediate stops and route alignments were to remain unspecified.

Service frequencies, which Volpe had suggested should align with demand, would not be disclosed.

Details about equipment for the service would not be shared with specificity.

No distinction would be made between “corridor” routes (<300 miles) and “long haul” routes.

It is unclear as to why Nixon chose Option #2, but given his already tepid interest in Railpax, it’s understandable to choose an option where you would receive “very low” blame for “killing” passenger rail service should this project fail in the long term.

Volpe Pushes Back (December 1970)

Unsurprisingly, the DOT did not support the limited system proposed by OMB and Nixon. After significant back and forth, additional endpoints were added to the plan, including routes from Chicago to San Francisco, Chicago to St. Louis, and St. Louis to Washington, D.C.

Despite these adjustments, the network left major gaps, particularly on the West Coast and in the Southeast. The New York Times, in December 1970, criticized the plan for its severe limitations, noting that it proposed only 16 intercity corridors, with nearly all routes radiating from New York City or Chicago4. Dissatisfied with the system, Congress proposed a six-month postponement of Railpax to allow time for the administration to reconsider and expand service.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), the federal transportation regulatory agency, also reviewed the plan and concluded that the preliminary plan did not comply with the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970. Specifically, the ICC found that the network failed to “continue and improve service between crowded urban areas and in other areas of the country.”5

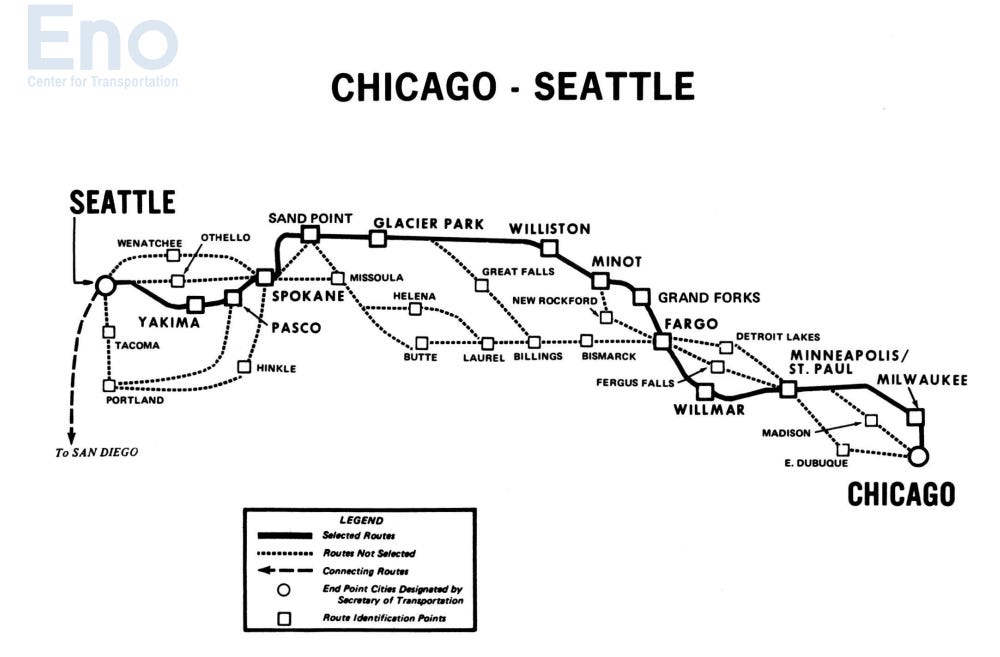

Based on these findings, the ICC recommended several additions to the network, including:

Maintaining passenger rail service on the West Coast between Seattle and San Diego.

Connecting the South and Southwest to the West with a thrice-weekly service between New Orleans and Los Angeles.

Ensuring the route between Chicago and San Francisco was as scenic as possible to attract passengers.

Providing a direct connection between Washington, D.C., and Chicago.

Routing trains between Chicago and Seattle via the Twin Cities.

Preserving rail service in Tampa Bay.

In response to these recommendations, the White House and DOT incorporated additional routes into the final system, including Cincinnati to Norfolk, Salt Lake City to Portland, and Boston to Chicago. International connections were also added—Seattle to Vancouver and New York City to Montreal—though these were not mandatory requirements. These adjustments aimed to address gaps in the system while balancing financial and political concerns.

McKinsey Makes the Final Decision (March 1971)

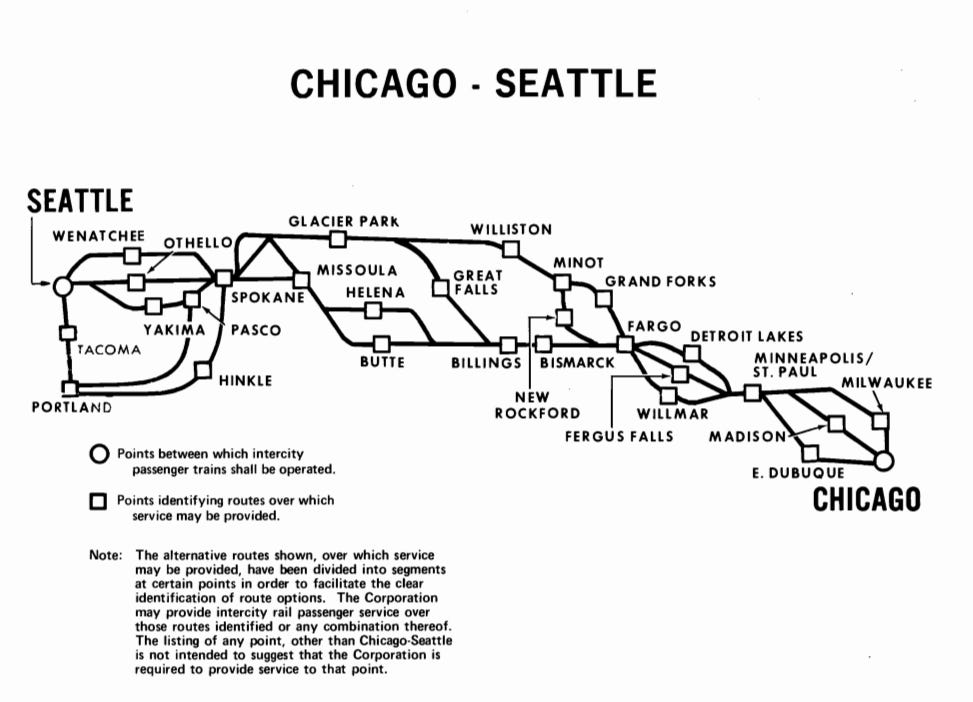

With the endpoints selected, the routing, which had been avoided until this point, now had to be finalized. For example, the route from Chicago to Seattle involved six different segments, resulting in 270 possible combinations. Determining the optimal routes for each segment was a monumental and highly political task.

After the final plan, including routing recommendations, was released on January 28, 1971, Secretary Volpe and the DOT faced a tight deadline: Amtrak had to be operational by May 1. To meet this challenge, the DOT enlisted an “army of consultants” from McKinsey. Tasked with the management and structural creation of the new rail passenger corporation, McKinsey developed detailed recommendations for routing, based on market size, physical characteristics, ridership potential, and profitability. Their work culminated in a comprehensive 273-page report outlining the proposed system in meticulous detail.

To establish a corporate identity for the new system, the DOT brought in branding experts Lippincott & Margulies, which created the name “Amtrak” by combining “America” and “track”.6 After months of negotiations, adjustments, and planning, America’s national rail system was finally born.

A New Beginning

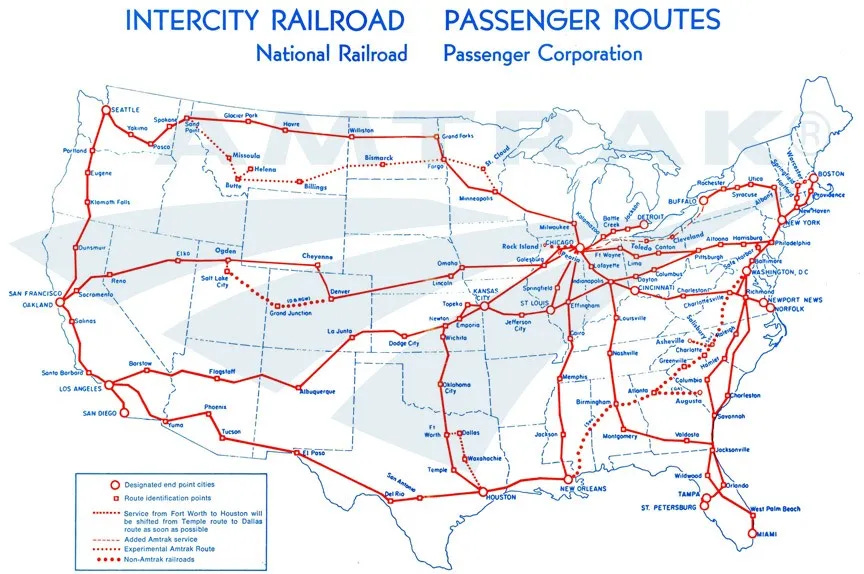

Of the 26 passenger railroads still offering intercity passenger rail service, six opted not to join Amtrak when operations began on May 1, 1971. Amtrak leased 1,200 of the best passenger rail cars from nearly 3,000 privately owned cars but owned none of its own tracks or rights-of-way.7 It wasn’t until the bankruptcy of Penn Central that Amtrak acquired the Northeast Corridor, and even today, in 2025, the corporation owns just 3% of the tracks it operates on.

Despite Nixon’s expectations, Amtrak has never turned a profit. Yet, in 2024, the corporation achieved its highest ridership year in its 53-year history, with 32.8 million riders—double the 16.6 million passengers from its first year—thanks in part to investments made under President Biden.

As our nation’s leaders reflect on the so-called “golden age of America,” let us not forget that this country and its communities were shaped and transported by the railroad. With investments in modernized infrastructure, expanded routes, and high-speed rail, we can usher in a “golden age of rail” that strengthens our economy, connects our communities, and offers a sustainable future for future generations—if we should be so lucky.

(Author’s note: The Eno Center for Transportation is an invaluable resource. Their historical document archive and articles were instrumental in helping me navigate the dense source material for this piece. Please consider using and supporting their efforts. Here are the two reports that guided me through the chronology of scanned memos and documents: one and two )

https://utahrails.net/pass/pass-timeline.php

https://about.usps.com/who/profile/history/pdf/mail-by-rail.pdf

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/01/16/archives/mechanical-bugs-still-plague-metroliners-after-year-in-service.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/12/06/archives/protests-made-over-gaps-in-railroad-passenger-plan.html

https://enotrans.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/1970-12-29-ICC-recommendations-on-DOT-plan.pdf

https://enotrans.org/eno-resources/1970-mckinsey-proposal-for-railpax-organization/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amtrak